The Field of Blackbirds and a Young Girl’s Notebook – a Moment That Remains with Me Today

Many of us can recall moments in our lives when time seemed to stand still: You experienced something so profound at that moment and it stayed in your mind, in all its details, whether it was a distressing or joyful moment.

For some individuals, these moments might occur more often than not, based on your profession. Police officers and first responders, medical professionals, pilots spring to mind first, as well as other careers where you just never know what you’ll experience during your shift. As someone who served in the military and the CIA and has responded to many disasters and supported war-time operations, my thoughts can easily wander from one unforgettable moment to another. While some memories stand out more than others, one particular moment in Kosovo still touches me today.

In my book The Protected I wrote about a particular moment from a protective operations assignment in Kosovo over 20 years ago.

The memories of that time came back very vividly not long ago when I read the news that the current President of Kosovo, Hashim Thaci, had resigned his presidency, with charges of war crimes hanging over him from when he was a guerrilla leader during the same period that I was in the country. I was reminded of a moment there regarding the human tragedy caused by wars, loss of life, and the innocent children who are victims, only to be forgotten by this world.

The following account best summarizes my experience back then (and is an excerpt from my book, The Protected):

Just weeks after the 1999 NATO coalition air campaign in Kosovo ended, our first team in the country established an initial base of post-war operations. I was on the second team, arriving on site a month later to provide relief and rotation for the first. Most Kosovar homes were damaged or destroyed after the opposing military passed through, leaving a path of utter destruction in their wake. The nearby power station had been damaged during the bombing campaign, so electricity and water at our base house could be hit or miss. At night, we would often be awakened by small arms fire and the occasional grenade being tossed at a nearby restaurant, home, or mosque where the local opposing religious and ethnic factions were still going at each other.

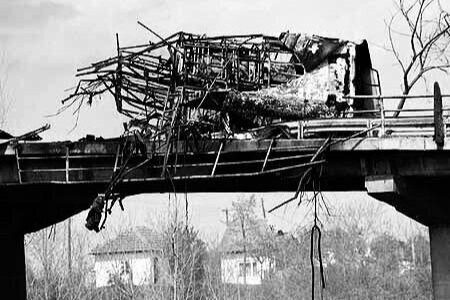

Photo by Reuters

A few weeks earlier, a NATO airstrike had accidentally hit a civilian bus in the town of Luzane, killing at least 34 people. The bus was split in half by the missile strike, one half still on the bridge and the other half laying approximately 35 meters below. Locals reported seeing several critically injured and many lifeless bodies lying all around, a number of them badly burned.

Tragically, the injured or dead included 15 children, though locals reported the numbers being much higher. When we arrived at the site, most of the debris had been removed, and what remained of the bus had been pushed off the bridge, where it now became part of the Kosovo landscape. There were no signs of casualties except parts of clothing scattered around and other small personal items that obviously belonged to the passengers. The acrid smell of burnt flesh and death still lingered. My mind quickly took me back to 1988 and the air show crash at Ramstein and another memory that is etched in my head for life.

Operating in the open and with the growing level of unwanted attention we were getting around the small capital town, we knew it was probably just a matter of time before we wouldn’t be safe anymore. Occasionally, we traveled to a part of town we affectionately named “Hogan’s Alley” (after the FBI’s tactical training facility, designed to provide a realistic urban setting for agents to use in live-fire tactical “shoot/don’t shoot” scenarios). This area was a street that had been bombed, burned, and looted – but one small café had been left partially intact. Only a few local patrons and perhaps various spies and agents working in the area would dine at this outdoor spot, yet this little café was the place to meet in the evenings for a simple margarita pizza, Coke and/or a cappuccino, which were the only items on the menu. It was always surreal to be sitting amongst the burned-out buildings, vehicles, and storefronts at small white plastic tables and chairs, heavily armed and watching all the “usual suspects” come out at night. Here, we would try to find a moment of normalcy in a time of confusion, death, chaos, and rebuilding as this little country was trying to find its new identity.

The Kosovo War, which had just ended, was one of the final conflicts in the breakup of the former Yugoslavia. Throughout the 1990s, the republics comprising the Serb-dominated country had broken off one by one. The 1992–1995 Bosnian War resulted in over 100,000 deaths, NATO intervention against Yugoslavia, and the reemergence of genocide in Europe. The Kosovo War between Yugoslavia and Kosovar Albanian separatists began in 1998; NATO intervened against Yugoslavia once more in 1999 after allegations of ethnic persecution against the local Albanians.

Ethnic conflict in this region wasn’t just a product of the 1990s breakup of Yugoslavia. As far back as the 14th century, another major battle was fought in Kosovo: “Kosovo Polje” (or “Field of Blackbirds” as it’s now known there). On June 15, 1389, the Ottoman Turkish army (led by Sultan Murad I) and Serbian army (led by Prince Lazar) met in a battle that resulted in the near-total destruction of both forces. Both commanders were killed, but the Ottomans came out on top, leading to the beginning of the end of Serbia’s independence. The Balkans continued to be a center of violence and instability in the centuries that followed.

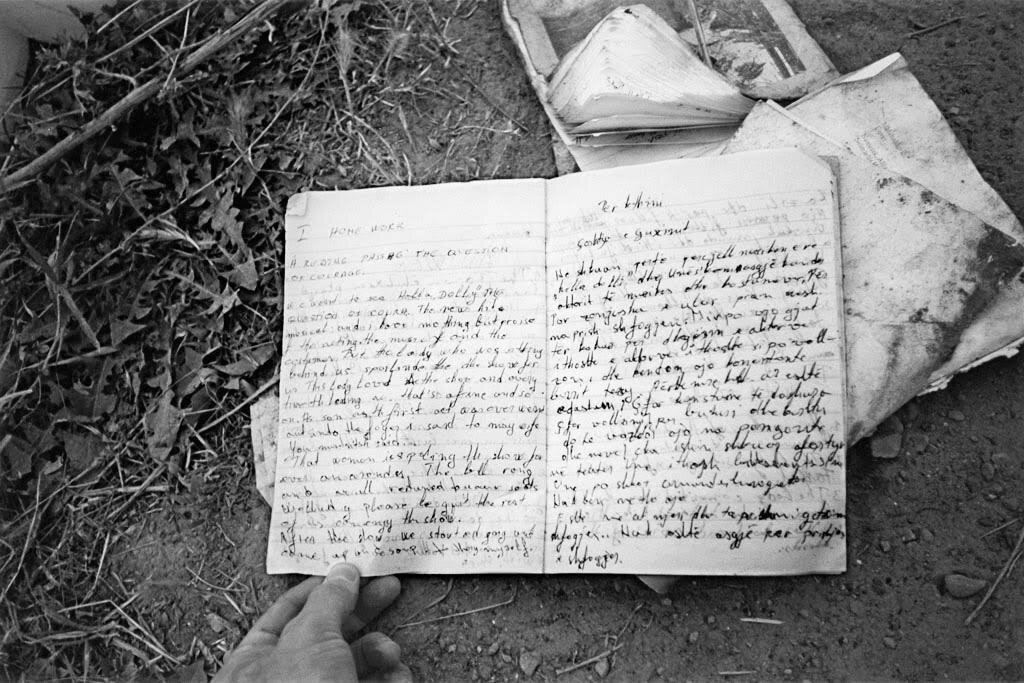

Photo taken by the author

Over 600 years after the Field of Blackbirds, I found myself walking the grounds where these wars were fought, across the places locals quote as “running red with blood” shed over this land for centuries.

Our missions went as far north as Mitrovica, one of my favorite parts of Kosovo, as it reminded me of some of the picturesque Bosnian landscapes where I had operated before. The southern end of our operations went as far as Skopje, Macedonia, where we would need to go on occasion for meetings and resupply – and for the only McDonald’s. While McDonald’s is not part of my normal diet, I must admit when you’re in a war-torn environment living on nuts and a few energy bars, a Big Mac and fries can taste really good.

Our travels would normally take us past the refugee camps near the Macedonian border, where Kosovars and others waited to return to their war-ravaged homes to see what was left.

For protective agents or anyone operating in a hostile foreign environment, area familiarization or “FAM” drives are essential and, in some cases, can be when we face our most dangerous exposure.

In 2011, an American security contractor was arrested in Pakistan and accused of killing two attackers during a FAM drive through the streets of Lahore. He was eventually released through intense negotiations a few months later. This incident exemplifies the inherent level of risk some of these operations can have – they’re not your normal EP missions.

Photo taken by the author

Back in Luzane, we walked down under the bridge where the bus was hit by the missile. As we did, I noticed a small paper notebook with handwritten notes in English. I realized the person to whom this little notebook belonged was practicing her English writing and translations. I surmised the little girl might have been fifteen years old, and I believed her name might have been Angela. She wrote of her time in school with her friends, who were Albanian, Serbian, and Turkish.

In one part of the notebook, she was practicing a letter to a pen pal somewhere in the United States describing her life in Kosovo. She wrote she had a family of six, and several brothers who weren’t in school yet. Her father worked in an office and her mother was a housewife. She described how she loved pop music and wanted to know what her pen pal’s favorite group was.

As I read, I couldn’t help but visualize this little girl riding the bus on this particular morning, maybe with a brother or sister or even her parents. She might have even been writing in this very book, unaware she only had a few seconds longer to live as a missile was inbound for her bus and would take her life and others on that morning.

I brought her notebook home with me and, several weeks later, I sat with my son (who was 12 years old at the time) and told him about where I found this book and what probably happened to this little girl.

I read a few pages to him and explained how this young girl was forced to mostly attend school underground due to the fact she was a Kosovar and under Serbian control. It was very difficult for children to attend school; often, their only option would be to attend secret classes at night.

Photo taken by the author

I had him keep this little girl’s book and would ask him to read it now and then to remind him how fortunate he was to freely attend school and learn openly without the fear of being attacked by a missile on the way there. I was never really sure how much he understood at that time, but for me, it was important to keep this little girl’s memory alive. I always tried to bring back a small piece of the world with me to give my son a global perspective, so he would realize how good his life was in our country.

You’re never really sure how much your child understands during those teaching years. My son has since spent many years himself in war-torn countries and witnessed similar events; he was fortunate to achieve a greater perspective after spending some time with locals who were trying to survive under unimaginable conditions. After returning home, he would say, “Dad, they just want the same thing we want – to be safe, have food, training, and opportunities to provide for their families and friends.” According to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, it’s what we’re all seeking. I know he gets it now, and I’m sure one day when the time is right he will convey his new perspective to his beautiful daughters.

I think Nelson Mandela summed it up when he said:

There can be no keener revelation of a society's soul than the way in which it treats its children.

~ Nelson Mandela

I still have this young girl’s notebook and occasionally take it out not only to recall that moment but, more importantly, to remember the millions of children who have been murdered, left homeless, abandoned, and abused by invaders and criminals during all wars and conflicts. Sadly, their millions of names and stories are lost to history, but on that day I promised not to forget the children on that bus who did not survive and who represented all the children who suffered during that war, the wars before and after, and those which unfortunately continue today.

— Mike